The Hunt for the Gravitational Wave Background

A sneakpeek into the efforts of an international team of scientists searching for one of the most elusive signals in the Universe.

This article is an english translation of the article written by Franziska Konitzer for the popular German magazine “Spektrum”.

I was interviewed for the article and you can read about what I had to say about the search for gravitational waves, along with many other prominent scientists in the field.

When black holes merge, their tremendous energy vibrates space-time itself. Detectors like LIGO measure these gravitational waves and have opened up a new observation window into the cosmos. But most of the time, black holes don’t collide, they just orbit each other. The gravitational waves generated fill the cosmos with an extremely deep hum: the gravitational wave background.

Experts are sure that there is this background signal of low-frequency gravitational waves in the cosmos. But the hunt for it is a kind of waiting game. It is known that these gravitational waves most likely exist. You know how to prove it. And then you start making observations, knowing that you’ll have to wait years and decades before you have the data to prove them.

A Puzzle with Pulsars

When LIGO proved in 2016 that gravitational waves really exist, Michael Kramer from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn had been waiting for quite a while. “Our data sets start in the mid-1990s,” he says. That’s how long he’s been keeping an eye out for low-frequency gravitational waves himself - not with a high-precision ruler like that of the LIGO observatory on Earth, but with the help of the extremely regular radiation pulses from distant pulsars.

Gravitational waves popped out of Einstein’s general theory of relativity as an unexpected side effect. Accelerated masses create ripples in spacetime. Einstein himself did not believe that it would ever be possible to prove the curious effect. It was to take around a century before mankind had created an experiment that is capable of doing just that: the LIGO observatory registers when a gravitational wave briefly compresses or expands the four-kilometre-long tunnels of its two facilities by the diameter of an atomic nucleus.

But as impressive as that is – the observation window it opens is tiny. Most of the gravitational waves are not visible to LIGO. Just like electromagnetic radiation, gravitational waves have a spectrum of different wavelengths and frequencies. A gravitational wave is all the lower-frequency and long-wave, the larger the masses that generate it.

The LIGO observatory and other gravitational-wave detectors can measure gravitational waves whose frequency would be in the audible range when converted to sound waves. Such waves are created in close binary systems of black holes and neutron stars that orbit each other and eventually merge.

However, there are much more massive objects in the universe than such stellar remnants. This means that there is still a lot of room down the frequencies in the gravitational wave spectrum. For example, not only normal black holes collide, but also the extremely massive black holes at the center of galaxies, which combine millions or billions of solar masses.

In order to measure their galactic collisions, the European Space Agency ESA would like to place a gravitational wave detector several million kilometers long in space: the Laser Interferometer Space Antenna (LISA) could detect gravitational waves there that arise when these cosmic giants merge.

Waves that are light years long

But even that only covers a fraction of the gravitational-wave spectrum. Because such collisions are extremely rare — most of the background noise gravitational waves are created in the millions and billions of years before the collision, as the extremely massive black holes orbit each other. The frequency range of their radiated gravitational waves is a few nanohertz. “These black holes need several years to orbit each other,” says Michael Kramer.

A few years can pass between two wave crests of such a gravitational wave. The gravitational-wave background, according to experts, consists of such sources - you can think of it as a low-pitched hum - while the gravitational-waves measured by LIGO are sometimes referred to as cosmic chirps. This hum requires detectors several light-years across. You can simply forget about building them yourself.

“Of course, building gravitational wave detectors for long-wave gravitational waves is not really realistic,” says Michael Kramer. After all, the universe provided a solution to the problem it posed, the puzzle’s main ingredient, so to speak: pulsars. Millisecond pulsars, to be precise.

Pulsar timing arrays: millisecond pulsars as gravitational wave detectors

Millisecond pulsars are former massive stars that, after the exciting days of nuclear fusion and shining, now spend their lives spinning around their own axes as neutron stars - hundreds of times per second. Such neutron stars are often equipped with a very strong magnetic field, with which they accelerate particles to extreme energies, so that they emit electromagnetic radiation, radio waves for example. When the magnetic pole and the axis of rotation are not perfectly aligned, as is the case with the Earth, this radiation sweeps the Earth at regular intervals. From our terrestrial perspective, the pulsar flashes in time with its extremely fast rotation.

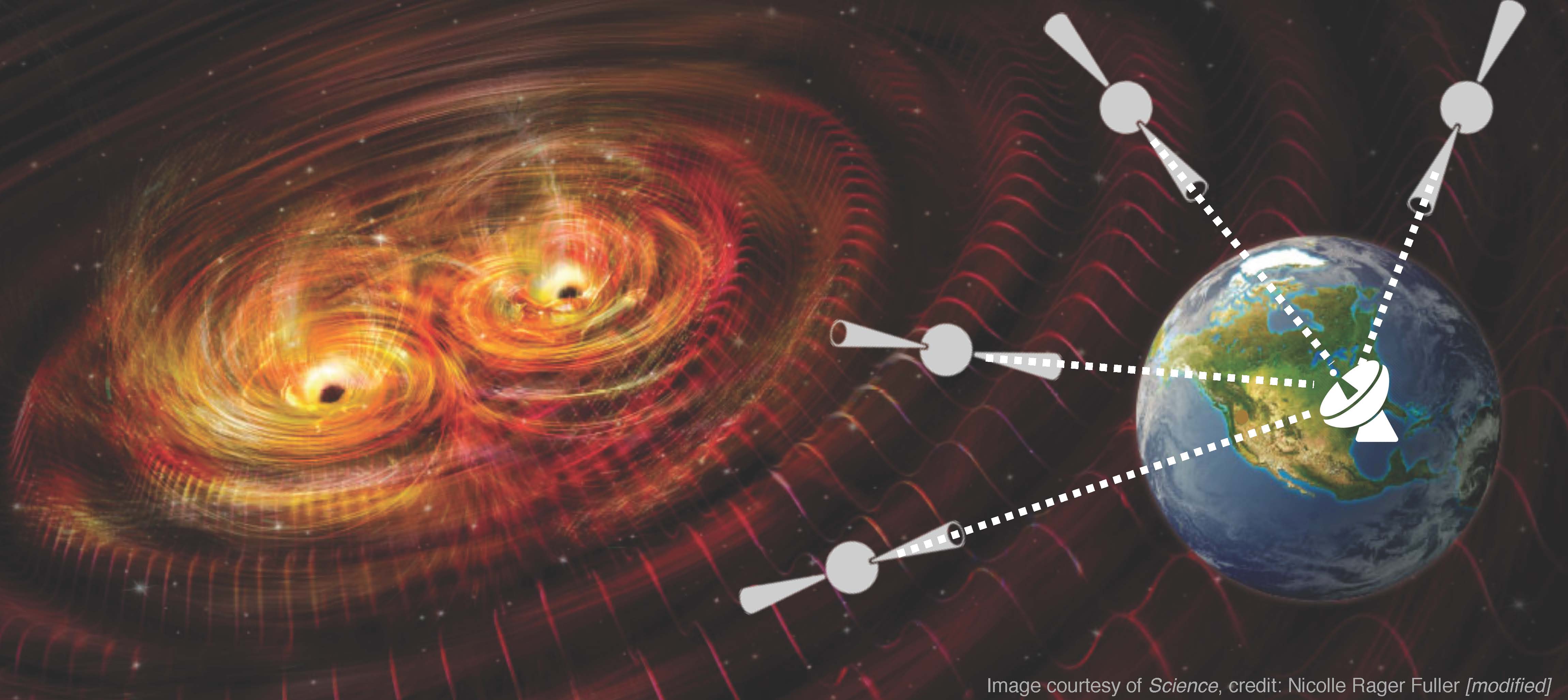

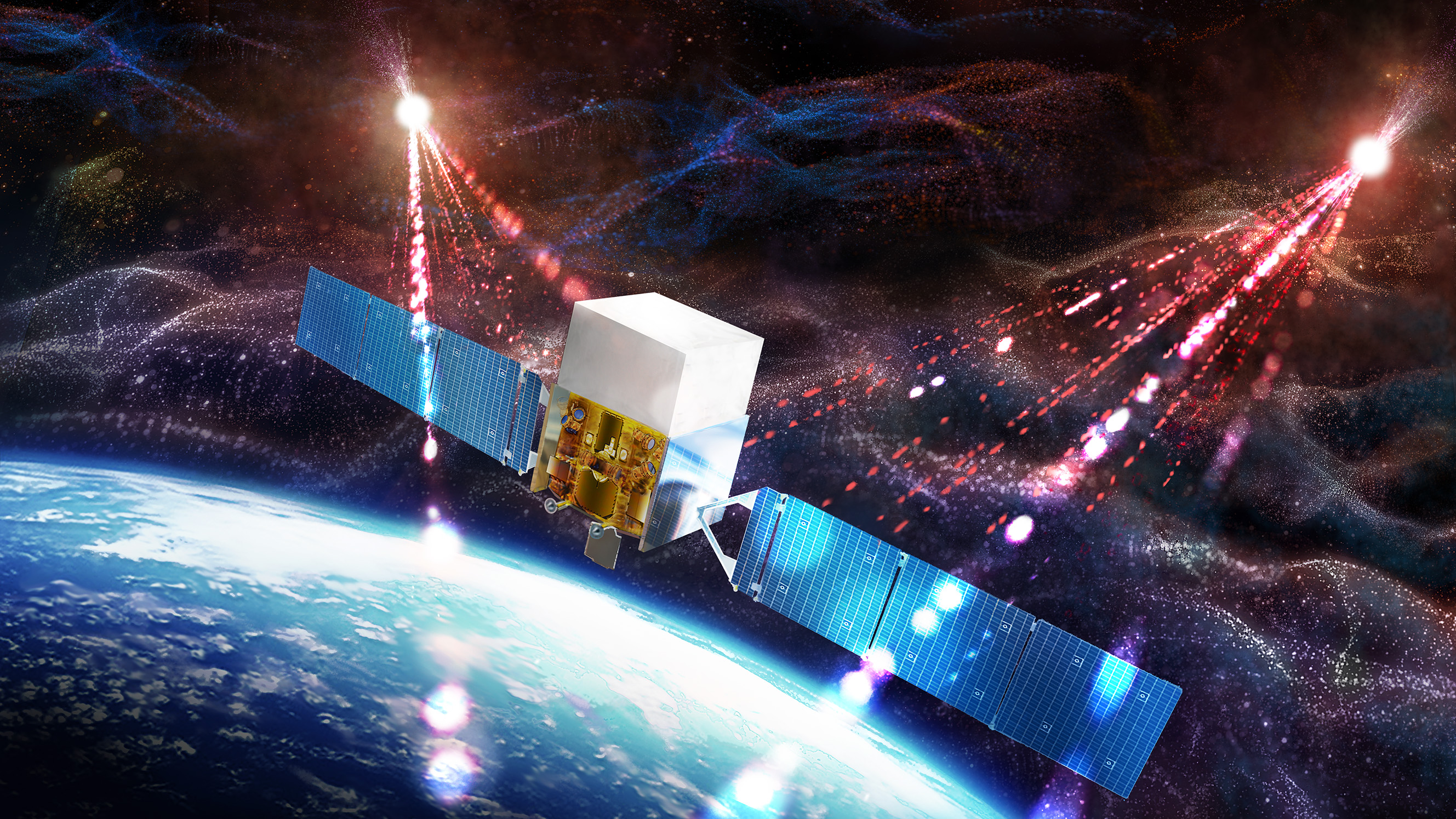

With EPTA on the hunt for gravitational waves | In the artist’s rendering everything looks quite simple - but in reality the search for the low-frequency gravitational-wave background is a highly complex matter.

In fact, it works so regularly that astronomers can predict the arrival time of the next pulse from a pulsar to a billionth of a second. Pulsars can rival some atomic clocks on Earth. And that’s why gravitational wave hunters like Michael Kramer don’t need a light-year-long ruler for their puzzle, but millisecond pulsars and a radio telescope.

He uses an experimental arrangement called “Pulsar Timing Arrays” (PTAs). They are based on the idea that nothing can disturb a pulsar except a randomly passing gravitational wave. It compresses and expands space-time itself. We on Earth notice this because the arrival times of the pulsar signals are treacherously shifted.

This is by no means as simple as it may sound. First of all, a single pulsar is not enough. That’s why you need the PTA from many such sources. In this, the researchers want to find patterns of how the changes in different pulsars in the sky are related to one another.

“You don’t just look at a pulsar in one direction in the sky and a pulsar in another direction in the sky, you have to compare them,” says Kai Schmitz, theoretical physicist at CERN. “You do that for as many pairs of pulsars as possible. And then when the data from all those pairs correlate in a certain pattern that’s spread across the sky, you can tell if they’re gravitational waves or not.”

In search of the Hellings Downs curve

Researchers call this pattern the Hellings-Downs curve. Put simply, she describes that the signals from pulsars that are close to each other or directly across from each other in the sky should be affected by gravitational waves in a similar way. The minimal changes in the arrival times of their signals should therefore be correlated with each other. On the other hand, pulsars that are more perpendicular to each other should show a negative correlation.

Given that the sought-after gravitational waves only settle down every few years, it was clear from the start that the search would take years. There are currently several pulsar timing arrays on Earth looking for the correlations. Michael Kramer is involved in the European Pulsar Timing Array EPTA, a coalition of five telescopes, including the 100-meter radio telescope in Effelsberg. There is also NANOGrav, a consortium founded in 2007, in the USA, and the Parkes Pulsar Timing Array in Australia.

The researchers involved are waiting for their time series to finally be long enough for the signal to crystallize. It’s not enough just to wait patiently.

During the measurement campaign, they reduce any uncertainty in the high-precision measurements as much as possible. For example, the one that arises because the center of mass of the solar system is not exactly known. Since the position of Jupiter in the solar system, for example, has not been determined with sufficient precision, there is still some uncertainty in the pulsar measurements.

In addition, the interstellar medium affects radio waves. Interstellar clouds of ionized gas scatter signals from the pulsars. In all this general noise, researchers are looking for a very specific noise. Not white noise, with all frequencies evenly distributed, but “red noise” with slightly lower frequencies, which would indicate that gravitational waves have altered pulsar arrival times.

Are gravitational waves hiding in red noise?

In 2021, the North American NANOGrav consortium announced that they had found the first indications of precisely those low-frequency gravitational waves from 12.5 years of data . Mind you: Nobody spoke of a discovery - because the error bars are still far too large. A Hellings Downs curve can only be recognized in the data with a lot of good will. Other research groups are therefore more cautious. “We’ve been seeing these clues since 2015,” says Michael Kramer. But, like the NANOGrav consortium, the group did not publish these results for the time being, although they have since made up for it . Finally, there is still a risk that the signal will go from red noise to white noise with even more data.

So far, at least, it doesn’t seem like the signal is going away. In January 2022, a coalition of all PTAs, the International Pulsar Timing Array IPTA, published an article in which they still could not announce a discovery - but more evidence of the hoped-for red noise. “There’s nothing wrong with the fact that these are actually gravitational waves,” says Kai Schmitz. “But we can’t pinpoint it yet because the error bars and the uncertainties are so large.”

And sometimes there are still unexpected developments even in this decades-long game of patience. For example, the good idea that Aditya Parthasarathy from the Max Planck Institute for Radio Astronomy in Bonn and his colleague Matthew Kerr from the US Naval Research Laboratory had: »We asked ourselves whether the pulses of the millisecond pulsars could also be detected in the gamma-ray range “, he says.

In principle, such pulsars not only send radio radiation into space, but they cover the entire electromagnetic spectrum.

Gravitational wave hunting now with gamma rays

High-energy gamma rays have an unbeatable advantage over radio waves: they are not impressed by the interstellar medium. In this respect, gamma radiation even offers an advantage over the high-precision measurements in the radio range, since this source of error does not exist there. On the other hand, gamma rays cannot be observed directly on Earth, since they are absorbed by the Earth’s atmosphere – fortunately for us, one has to say.

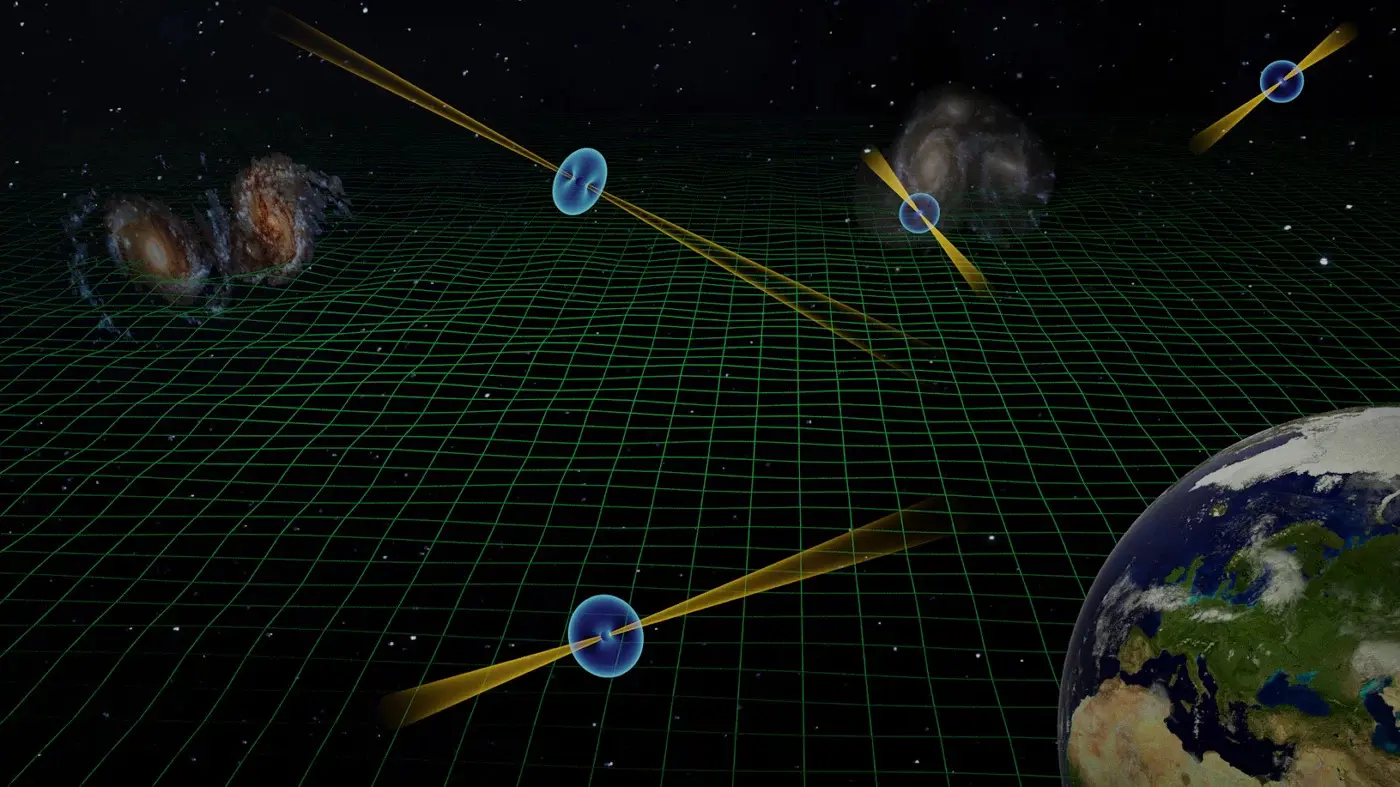

The Fermi Large Area Telescope (LAT) on the Fermi satellite | Researchers can also hunt for the low-frequency gravitational wave background in the gamma-ray range. How convenient that a gamma-ray space telescope has been in Earth orbit for several years.

Fortunately, there is a gamma-ray telescope in Earth orbit, where this radiation can easily be received: the Fermi space telescope has been observing the high-energy sky since 2008. Aditya Parthasarathy and Matthew Kerr wondered whether the gravitational-wave signal from the millisecond pulsars could in principle also be detected in the gamma-ray range. The answer: Yes, you can. As a result, twelve years of data were available to the experts in one fell swoop. The Fermi-LAT collaboration recently published the results in the journal Science .

“And the good thing is that we don’t even have to do that much because Fermi is in Earth orbit and is scanning the whole sky from there,” says Aditya Parthasarathy. “It works so well that we could even detect the low-frequency gravitational waves all by ourselves, without the PTAs in the radio wave range. It is a completely independent method.«

However, Aditya Parthasarathy still has to be patient. Although he and his team were able to show that the method works in principle, they simply haven’t collected enough data yet. And so it is also for the gravitational wave hunters in the gamma ray range: Welcome to the waiting.

As researchers wait for the first data on the gravitational-wave background, they ask themselves what they might actually be observing. What creates the gravitational wave signal? Because it’s not the hum of a single pair of merging black holes that describes the Hellings Downs curve. Instead, it is a superimposed signal from many extremely massive black holes that migrate to the new common center when two galaxies collide and orbit each other there. That is why researchers also speak of the stochastic gravitational wave background.

If black holes are too boring for you, how about cosmic strings?

However, other processes in space could also generate such low-frequency gravitational waves. The theoretical physicist Kai Schmitz deals with them. He would like to be on the lookout for signs of cosmic strings, remnants of the universe’s time just after the Big Bang. Such cosmic strings could be indicative of phase transitions our cosmos was undergoing at that time - and they would be a direct indication of physics beyond the Standard Model. Or maybe the Hellings-Downs curve even hints at the cosmic inflation shortly after the Big Bang, which caused space-time itself to oscillate?

This all sounds more complicated than it is. Ultimately, the pulsar timing arrays are about being able to detect gravitational waves at all. We can talk later about exactly what was proven there. “First you have to tick the Hellings-Downs curve,” says Kai Schmitz.

Because only when the curve emerges in the data for the coming years will further questions arise. One could then, for example, analyze the spectral distribution, i.e. which frequencies are involved and to what extent. This could reveal whether the gravitational waves hold a cosmological secret from the beginning of the universe - or whether they are of astrophysical origin. In the latter case, the background noise would indicate a process that researchers are almost certain exists: the merger of supermassive black holes in merging galaxies.

“Over the next few years, with more data, the error bars will shrink. And if the error bars then decrease in the direction where you would like them to be, there is great hope that the signal for the gravitational waves will become apparent,” says Kai Schmitz. He even hopes that the signal is hiding even now in the few years of data that has already been collected but not yet analyzed. Then it wouldn’t be long before the gravitational-wave hunters could announce a discovery.

Other researchers like Aditya Parthasarathy are not so optimistic: “I think we should be careful at this point,” he says. “These are extremely weak signals. I think it will be a few more years before we actually have a result.’ Still, Parthasarathy speaks of years, not decades. So the waiting game in the hunt for the gravitational waves continues for the time being - but maybe not for much longer.